SPACs: Not So SPACtacular

February 3, 2021

By Jon Henschen, WealthManagement.com

Blank check companies are a great deal—for their sponsors. For investors? The results so far have been abysmal, argues Jon Henschen.

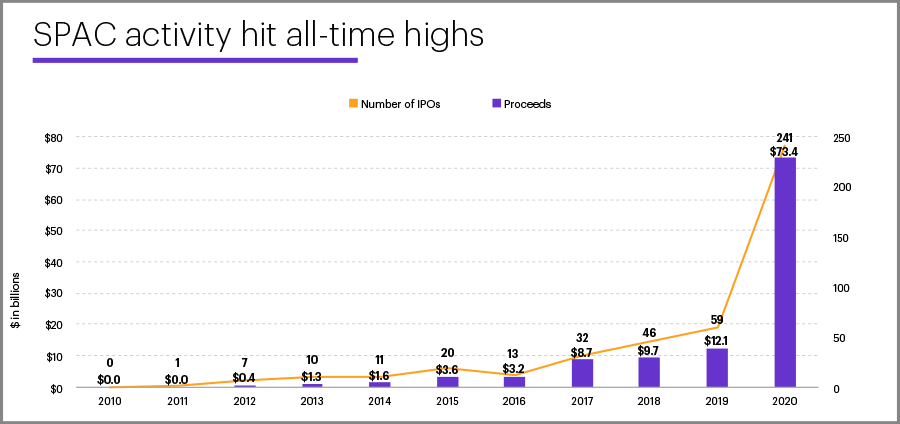

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies, or SPACs, have been on a hockey stick growth chart since 2016. This alternative method of going public versus the traditional IPO process has been getting the attention of RIAs and broker/dealers such as Cetera’s Adam Antoniades, who has said SPACs may be a viable consideration for that firm going public.

Longstanding IBD executives are also now directly involved with SPACs. That includes Larry Roth, who has held the CEO spot at both Cetera and Advisor Group, now raising capital for Britain-based Kingswood Holdings, whose blank check company Kingswood Acquisition Corp. recently went public with the intention of using raised capital to firms in the fast-growing wealth management space.

SPAC Transaction Summary 2010-2020

Source: Renaissance Capital. Includes SPACs listing on the Nasdaq/NYSE/AmEx with a market value above $50 million. Excludes over-allotments. Includes SPACs currently scheduled to price before 12/31/20.

Many SPACs use the services of a well-known person for promotion, where the celebrity touts that they are a primary investor in, or sponsor of, the SPAC, such as basketball icon Shaquille O’Neal.

When a company goes public through the traditional IPO process, regulations like the SECs “Regulation M” mandate a quiet period that restricts the company from going out to the public and taking a sales-hype approach to drum up interest. SPACs, on the other hand, have no such restrictions. They can go to the media and put sales hype into overdrive.

SPACs raise capital for an IPO in order to, in the future, buy a private company with common stock at a common price of $10 per share and a warrant that gives investors preference to buy more common stock at a later date at a fixed price.

While SPAC sponsors look for a company of interest, the raised funds are kept in a trust, with a two-year timeline to invest the money. If the money is not invested, the SPAC will be liquidated and the proceeds returned to investors.

The primary driver as to why the growth of SPACs have been so dramatic is the compensation model of “twenty and two.” Most SPAC sponsors receive 20% of the equity in the post IPO company, a feature known as the “sponsor promote.” They can purchase warrants that allow them to increase that ownership level. They also earn a 2% ongoing fee on the assets, regardless of how much the fund makes or loses. A fund that raised $1 billion of assets would generate $20 million of fees for the sponsor annually.

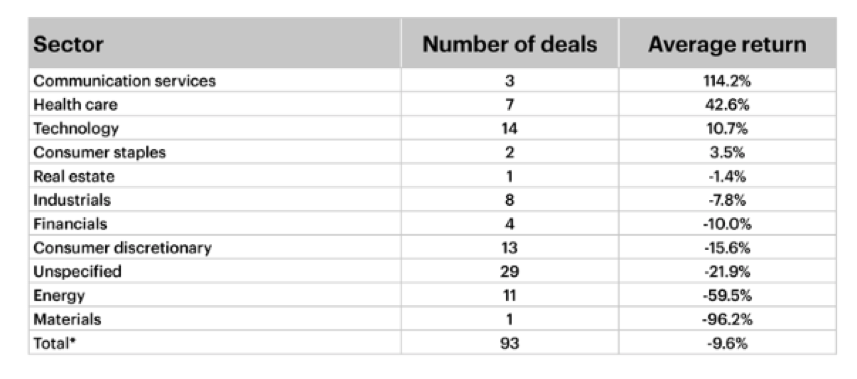

Are SPAC costs worth these high fees due to SPACtacular performance? The following chart answers that question.

SPAC Performance by Sector Post-Acquisition

Source: Renaissance Capital. Target section identified at time of IPO; may differ from sector of acquired company. “Number of SPACs that have completed mergers and taken a company public, 2015-10/1/20.

With a total of 93 deals, we see an average return of -9.6%, which makes you question, “Why are these products so popular?”

Jesse Felder, publisher of The Felder Report and co-founder, VP, and head trader of a multi-billion-dollar hedge fund Aletheia Research & Management, says that SPACs have proven to be some of the worst investments you can own. Felder believes they are borderline fraudulent and that it is only at the height of speculation mania that you would see an appetite for SPACs as we see today. When you look at the compensation, it’s no wonder everyone wants to start their own SPAC.

Hedge fund managers like Jesse Felder have an investing edge due to expertise at analyzing and managing quantitative data. When we see people like former Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, basketball player Shaquille O’Neal, Billy Beane of Moneyball fame or astronaut Scott Kelly touting a SPAC on CNBC, it isn’t an investing edge they possess but rather a sales edge.